The New York City Council Committee on General Welfare recently held a hearing on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on SNAP Administration, Food Pantries, and Soup Kitchens. NYHealth submitted the following written testimony on the pandemic’s impact on food security in New York.

September 23, 2020

Chairperson Levin and distinguished members of the Committee on General Welfare:

The New York Health Foundation (NYHealth) appreciates the opportunity to submit written testimony regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SNAP administration, food pantries, and soup kitchens in New York City.

As of mid-September 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has killed more than 19,000 and sickened 235,000 New York City residents.[1] A dire consequence of the resulting economic recession is the impact on food security. Mass losses in employment in the City have curtailed New Yorkers’ ability to afford food. Stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures have also cut off reliable pathways to food access, such as meals provided in community settings (e.g., houses of worship, senior centers). Many New Yorkers have been forced to choose between their need for food and their own sense of safety, given the risks of contracting or spreading COVID-19 while accessing food during the pandemic. In these extraordinary circumstances, funding programs and supporting sound policies to improve food security are more vital than ever before.

NYHealth’s Work to Improve Food Security

NYHealth is a private, independent foundation that works to improve the health of all New Yorkers, especially the most vulnerable. Our work has provided us with in-depth knowledge of food insecurity’s widespread ramifications for the health of children, families, and the communities they live in. In particular, our Building Healthy Communities program supports expanding access to nutritious, affordable foods.

Since 2014, we have invested millions of dollars to improve food security across the State. NYHealth has supported the creation of more than 85 new healthy food access points like farmers markets, mobile markets, and grocery and corner stores; supported the establishment of regional food hubs in New York City and the North Country; expanded access to and demand for nutritious, affordable foods, including nutrition incentive programs that encourage Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) use; and partnered with the Mayor’s Office on its Building Healthy Communities initiative. NYHealth’s support to Community Food Advocates also helped secure universal free school lunch for New York City’s 1.1 million public school children.

Since March 2020, NYHealth has committed an additional $5 million to support COVID-19 response efforts, with a significant proportion of these dollars being directed toward organizations that ensure New Yorkers have the healthy food they need. This includes an assessment by three of New York’s leading independent food policy research centers (the Laurie M. Tisch Center for Food, Education, and Policy; the City University of New York Urban Food Policy Institute; and the New York City Food Policy Institute at Hunter College) that will monitor and assess the response to COVID-19 by New York City’s food system. As the pandemic unfolds, both new threats and opportunities will emerge. It is important to start now to assess, monitor, and compile evidence about what works and what doesn’t. This research will help policymakers and advocates to effectively and equitably implement new programs and policies that chart safe paths to restoring food security and the regional food economy.

Using several recently developed City, regional, and State food plans as a starting point, the collaborative will explore how existing and new COVID-19-related programs contribute to achieving goals such as: reducing food insecurity, ensuring access to healthy affordable food, restoring the local and regional food economy, and protecting food workers. In fact, the collaborative will be holding a public forum on September 30th to present actions that public officials and agencies, civil society groups, and others can take to minimize the harms and maximize the opportunities to address the underlying problems the pandemic has exacerbated.[2]

NYHealth grantees that connect New Yorkers to a range of benefits and services tell us that their clients are overwhelmingly requesting food ahead of any other need. Federal data confirm this trend; according to Hunger Free America, SNAP enrollment in New York City in April 2020 increased by nearly 69,000 people—the largest one-month jump ever.[3]

NYHealth regularly collaborates with the New York City Mayor’s Office and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene on efforts to improve food security across the City. NYHealth applauds the City’s continued recognition and focus on the role that access to healthy food plays in maintaining good health and preventing disease, especially in response to COVID-19. The City has worked rapidly to launch new initiatives to ensure that New Yorkers have access to food, as well as to support businesses and farms in supplying and distributing food across the State. The GetFoodNYC Covid-19 Emergency Food Distribution Program, for example, has distributed millions of meals throughout the City since April. Additionally, the Mayor’s Taskforce on Racial Inclusion & Equity recently announced new food access programs in neighborhoods that have suffered disproportionately during the pandemic.

New Data on New Yorkers’ Food Scarcity During COVID-19

At this critical juncture, NYHealth would like to provide the Committee with new data that sheds light on the growing and stark food insecurity challenges facing New Yorkers. Although this is a State-level analysis, it can support the City in its continued efforts to design programs and target resources, as well as provide data when working with State and federal partners.

The data presented here are from an upcoming NYHealth analysis based on the COVID-19 Household Pulse Survey, which is administered by the U.S. Census Bureau in collaboration with multiple federal agencies. The survey provided near real-time data on household experiences, including with food scarcity, during the coronavirus pandemic from April 23, 2020, until July 21, 2020. The survey makes it possible to produce estimates by state, including by race and ethnicity, age groups, and income categories. It also assesses the degree to which New Yorkers accessed free meals and groceries, where they did so, and whether they used federal stimulus checks for food-related expenses. Further information about the survey is available on the Census Bureau website.[4]

Below are key findings from the NYHealth analysis of the COVID-19 Household Pulse Survey data for New York State. Many of the findings highlight the increasing food scarcity rate, which is defined as the percentage of the adult population in households that either sometimes or often did not have enough to eat in the last seven days. The analysis also indicates how different groups of New Yorkers are accessing free meals and groceries and from which access points.

Food Scarcity

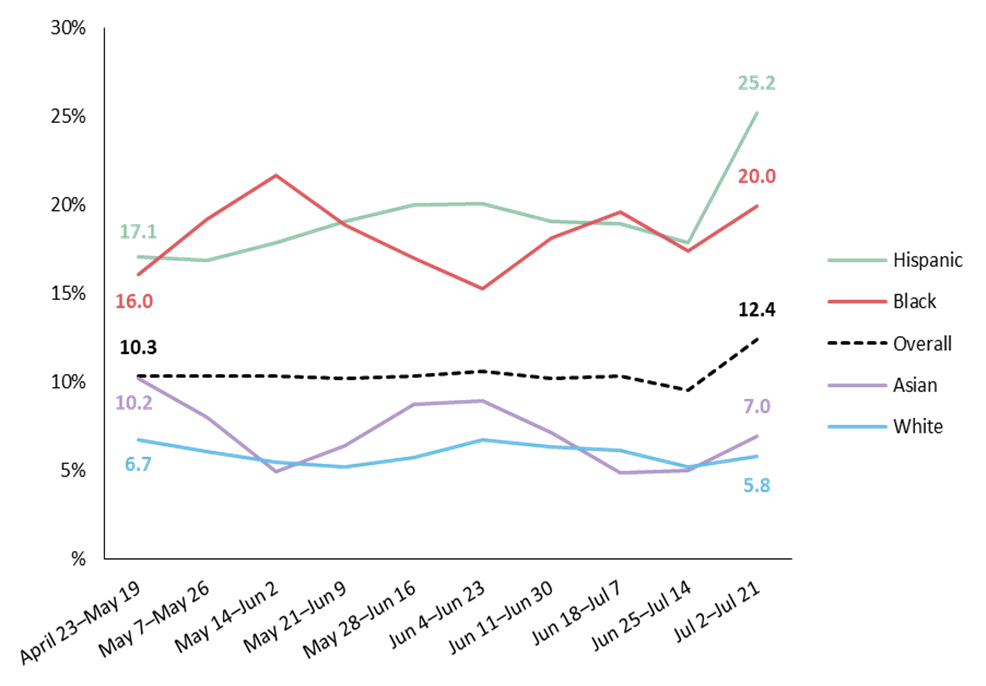

- From April through June, approximately 1 in 10 New Yorkers reported household food scarcity in the prior week. There was an uptick in food scarcity in July, when the rate surpassed 12% (see Exhibit 1). The food scarcity rate in New York State was generally consistent with the national rate, but higher than those reported in neighboring states.

- A larger proportion of households with children experienced food scarcity than households without children.

- There are stark disparities in food scarcity by race and ethnicity. Between 17% and 25% of Hispanic New Yorkers and 15% and 22% of Black New Yorkers experienced household food scarcity over the survey period. These percentages were three to four times higher than among white New Yorkers (see Exhibit 1).

- Food scarcity is increasingly affecting households that did not struggle to access food prior to the pandemic. In April, nearly one-quarter of adults in households with food scarcity reported being food sufficient prior to the pandemic; but by July, that figure had risen to more than one-third of respondents.[5]

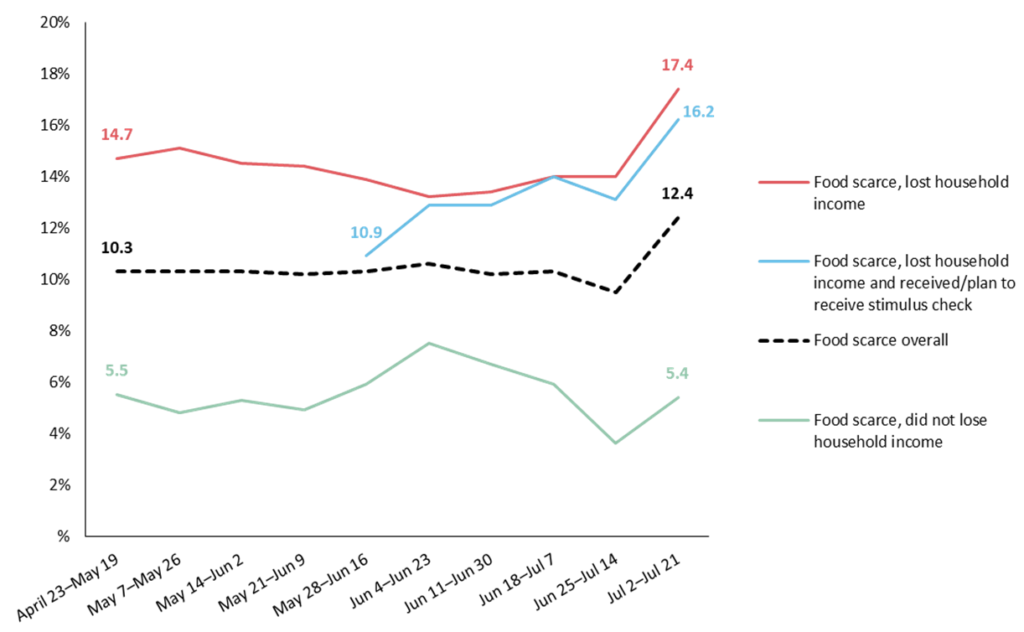

- Mass losses in employment have likely contributed to increases in food scarcity. Nearly 60% of New Yorkers reported in July that they or someone in their household had lost employment income since the start of the pandemic. In July, the rate of food scarcity was higher (more than 17%) for those who reported lost household employment income during the pandemic in comparison to those who did not (5%) (see Exhibit 2).

- The federal Economic Impact Payments—known as stimulus checks—did not appear to make much difference in the food scarcity rate for those who reported lost employment income (see Exhibit 2). This raises concern that benefit programs such as stimulus checks and Pandemic Unemployment Assistance may not be enough to keep some New Yorkers food sufficient.

Free Meal & Grocery Use

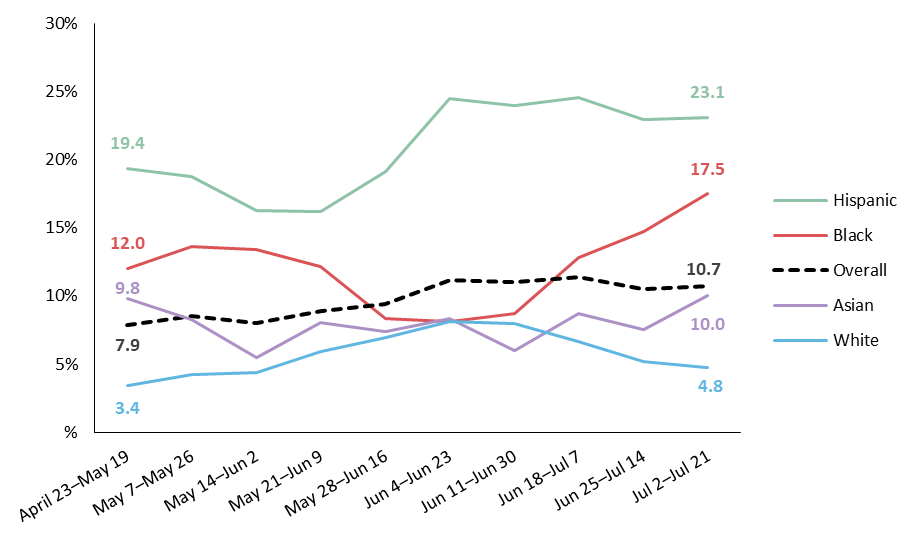

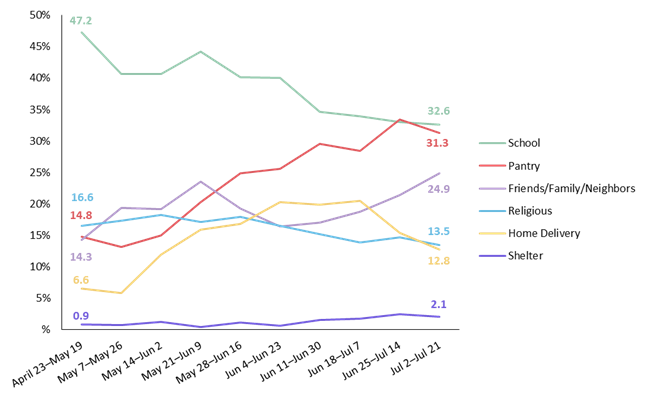

- In July, nearly 11% of New Yorkers reported that their households were accessing free meals or groceries (see Exhibit 3). School programs and food pantries were the most used access points overall (see Exhibit 4).

- Hispanic and Black adults were consistently more likely to report that their households accessed free meals or groceries in the prior week over the survey period, compared to white and Asian adults (see Exhibit 3).

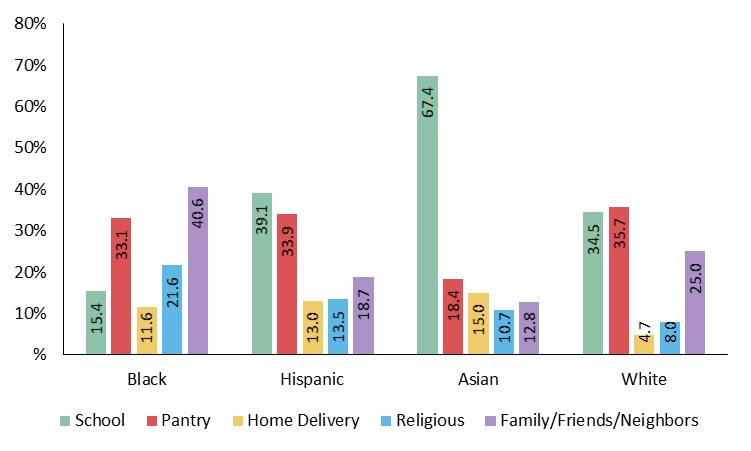

- There were differences in where people accessed free food and groceries by race and ethnicity. In July, Black New Yorkers were most likely to identify friends/family/neighbors and pantries as their household access points for free food and groceries. Meanwhile, Hispanic and white New Yorkers were most likely to identify school programs and pantries, and Asian New Yorkers were most likely to identify school programs (see Exhibit 5).

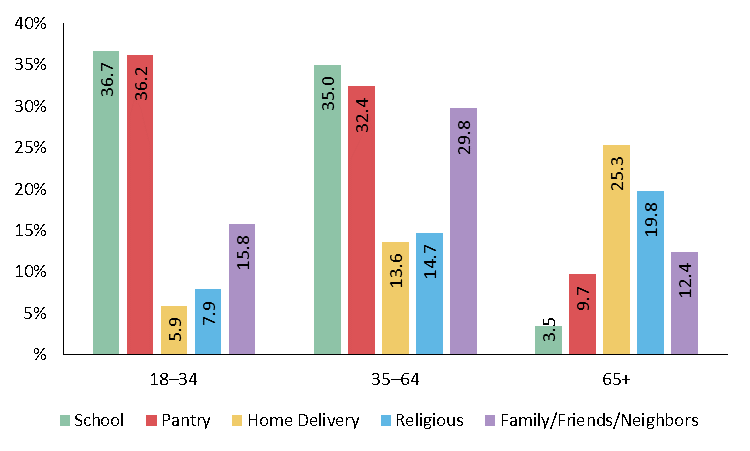

- By July, young adult and middle-aged New Yorkers reported their households accessed free food and groceries through school programs and pantries more than any other source. Home delivery was cited most frequently by elderly adults (see Exhibit 6).

In summary, food scarcity in New York is high relative to other states and increased during the coronavirus pandemic. An increasing share of food-scarce New Yorkers are newly food scarce, and therefore may require enhanced outreach and support in enrolling in food assistance programs for the first time. The dramatic disparities in food scarcity by race and ethnicity also indicate that current food assistance programs are not sufficiently addressing the needs of communities of color. Finally, the popularity of schools and pantries as access points for free food and groceries can potentially inform the design of food assistance programs.

Moving Forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended almost every aspect of New York City’s food system. As the implications of increased food insecurity continue to evolve, we offer the following recommendations:

- Expand policy solutions that make it easier and more convenient for New Yorkers to access food, including:

- Supporting public education campaigns that increase awareness of and enrollment in The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and SNAP, using trusted messengers;

- Making nutrition incentive programs (e.g., New York City’s Health Bucks or Double Up Food Bucks, which can double the value of federal food benefits, such as SNAP, at participating markets and grocery stores) available for use in more supermarkets; and

- Supporting citywide expansion of the Good Food Purchasing Program and the creation of regional food plans, building upon NYC’s recent codification of the Office of Food Policy and requirement for a 10-Year Food Plan, to better understand and strengthen our food systems.

- Work with partners at the State level to maximize currently available flexibility in nutrition benefits programs, including SNAP and WIC. The City should advocate for the State Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance and the State Department of Health to continue to leverage opportunities, including extended re-certification timelines for benefits, removal of barriers to enrollment (e.g., SNAP enrollment interviews), and expansion of the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot. Early results from the pilot program showed that adoption of online grocery shopping has the potential to improve healthy food access for low-income consumers. This past summer, the State legislature passed a bill that would expand the online purchasing pilot, and it is awaiting delivery to the Governor.[6]

- Support New York federal elected officials in advocating for the extension of Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer and WIC COVID-19 waivers past September, which would require congressional action. Additionally, support New York federal elected officials in maintaining the continued extension of SNAP emergency allotments.

- Minimize hurdles for community-based organizations and human services agencies working on the frontlines by quickly addressing contracting and payment delays that impede their abilities to retain staff and deploy resources.

- While immediate attention must focus on meeting the food access needs of New Yorkers during the pandemic, the City should continue to implement long-term sustainable solutions for an equitable and just food system, including the City Council’s support to codify the Good Food Purchasing Program through legislation.

- Collect and assess data to understand the depth of the crisis across the City. NYHealth plans to share our full analysis described above with the Committee via email upon the report’s publication. We are available to discuss performing additional analyses that may be helpful to the Committee. A second phase of the Census Bureau survey began in mid-August and will collect data through the end of October.[7] We plan to publish an updated analysis of food scarcity that will include this second time period.

NYHealth is grateful for the shared recognition among stakeholders of the role that healthy food access plays in contributing to healthy people, as well as promoting vibrant neighborhoods and stronger local economies. We look forward to continuing our partnerships with the City and other anti-hunger organizations that are working to lift up food security programs that we know work, and that support the health of New Yorkers and the New York City economy.

Appendix – Data Tables and Graphs

Exhibit 1. Food Scarcity in New York State

Percentage of adults in New York households where there was either sometimes or often not enough to eat in the last seven days.

Note: For overall rate, all adults who responded to food scarcity question are included in the denominator. For rates by race/ethnicity, age, income, and state categories, only adults in each respective category who responded to food scarcity question are included in the denominator. Rates are calculated across a three-week period.

Source: NYHealth analysis of U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey. U.S. Census Bureau. “Household Pulse Survey Public Use File.” Accessed September 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html

Exhibit 2. Food Scarcity by Household Employment Income Loss

Percentage of adults in New York that lost/did not lose household employment income since March 13, 2020 who reported household food scarcity in the last seven days.

Note: For overall rate, all adults who responded to food scarcity question are included in the denominator. For rates by household employment income loss/no loss, all adults who responded that they did/did not experience a household employment income loss are included in the denominator. For rates by household employment income loss and Economic Impact Payment (stimulus check) receipt, all adults who responded that they experienced a household employment income loss and that they or someone in their household received or plan to receive a stimulus check are included in the denominator. Stimulus check data are available beginning the week of May 28, 2020. Rates are calculated across a three-week period.

Source: NYHealth analysis of U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey. U.S. Census Bureau. “Household Pulse Survey Public Use File.” Accessed September 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html

Exhibit 3. Free Meals & Groceries

Percentage of adults in New York households that received a free meal or groceries in the last seven days.

Note: For overall rate, all adults who responded to free meal and grocery question are included in the denominator. For rates by race/ethnicity, age, income, and state categories, only adults in each respective category who responded to free meal and grocery question are included in the denominator. Rates are calculated across a three-week period.

Source: NYHealth analysis of U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey. U.S. Census Bureau. “Household Pulse Survey Public Use File.” Accessed September 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html

Exhibit 4. Free Food Access Points

Percentage of adults in New York households that accessed free meals or groceries in the last seven days at a particular food access point (categories not exclusive).

Note: All adults who responded that their household accessed a free meal or groceries in the preceding seven days are included in the denominator. Respondents could select multiple answers for where they or someone in their household accessed a free meal or groceries. Not all access sites are included because of low counts. Some school programs offered free meals via delivery, so some home delivery responses might be part of a school program. Responses for shelters may be artificially low, because the populations that most use shelters may have been less likely to have had access to a cellphone or email to be part of the survey sample. Rates are calculated across a three-week period.

Source: NYHealth analysis of U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey. U.S. Census Bureau. “Household Pulse Survey Public Use File.” Accessed September 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html

Exhibit 5. Free Food Access Points, by Race/Ethnicity, July 2–21, 2020

Percentage of adults in New York households that accessed free meals or groceries in last 7 days that used a particular food access point (categories not exclusive).

Note: Adults in each respective race or ethnicity category who responded that their household accessed a free meal or groceries in the preceding 7 days are included in the denominator. Respondents could select multiple answers for where their household accessed a free meal or groceries. Not all access sites are included due to low counts. Some school programs offered free meals via delivery, so some home delivery responses might be part of a school program. Rates are calculated across a three-week period.

Source: NYHealth analysis of U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey. U.S. Census Bureau. “Household Pulse Survey Public Use File.” Accessed September 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html

Exhibit 6. Free Food Access Points, by Age, July 2–21, 2020

Percentage of adults in New York households that accessed free meals or groceries in last 7 days that used a particular food access point (categories not exclusive).

Note: Adults in each respective age category who responded that their household accessed a free meal or groceries in the preceding 7 days are included in the denominator. Respondents could select multiple answers for where their household accessed a free meal or groceries. Not all access sites are included due to low counts. Some school programs offered free meals via delivery, so some home delivery responses might be part of a school program. Rates are calculated across a three-week period.

Source: NYHealth analysis of U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey. U.S. Census Bureau. “Household Pulse Survey Public Use File.” Accessed September 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html

[1] New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. “COVID-19 Data.” Accessed September 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page

[2] Event information is available at : https://www.cunyurbanfoodpolicy.org/events/2020/9/30/webinar-ny-food-2020-visions-research-and-recommendations-for-food-systems-during-covid-19-and-beyond.

[3] Hunger Free America. “In April, NYC had largest one-month actual increase in SNAP food aid participation in modern history.” Press Release. June 10, 2020. https://www.hungerfreeamerica.org/blog/april-nyc-had-largest-one-month-actual-increase-snap-food-aid-participation-modern-history

[4] U.S. Census Bureau. “Household Pulse Survey.” Accessed September 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/household-pulse-survey.html.

[5] Food sufficiency prior to the pandemic is defined as a household having enough of the kinds of food wanted or having enough food, but not always the kind wanted, before March 13, 2020.

[6] S. 8247A, 2020 Leg., 2019-2020 Sess. (N.Y. 2020).

[7] U.S. Census Bureau. “Household Pulse Survey – Phase 2.” Accessed September 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/household-pulse-survey.html